-

Posts

822 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

4

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Static Pages

News

Blogs

Gallery

Events

Downloads

Posts posted by Bryaxis Hecatee

-

-

I'll tell you as I'll be at the villa on the 23rd

-

1

1

-

-

Well I'd presume a good concordance search for the words palaestina could help identify all occurences of the word and even potentially it's link with syria, providing one with the sources. other than that a book such as the OCD (Oxford Classical Dictionnary) or a sum such as the good old Pauly-Wissowa Real Encyclodie der Altertums Wissenshaften should also be able to help here

-

Le Bohec's led encyclopedia looks to be something I'd like on my shelves, but damn the price !

-

1

1

-

-

Krentz' book and the Buraselis/Meidani books would be my two first choices, with Fink's as a third

-

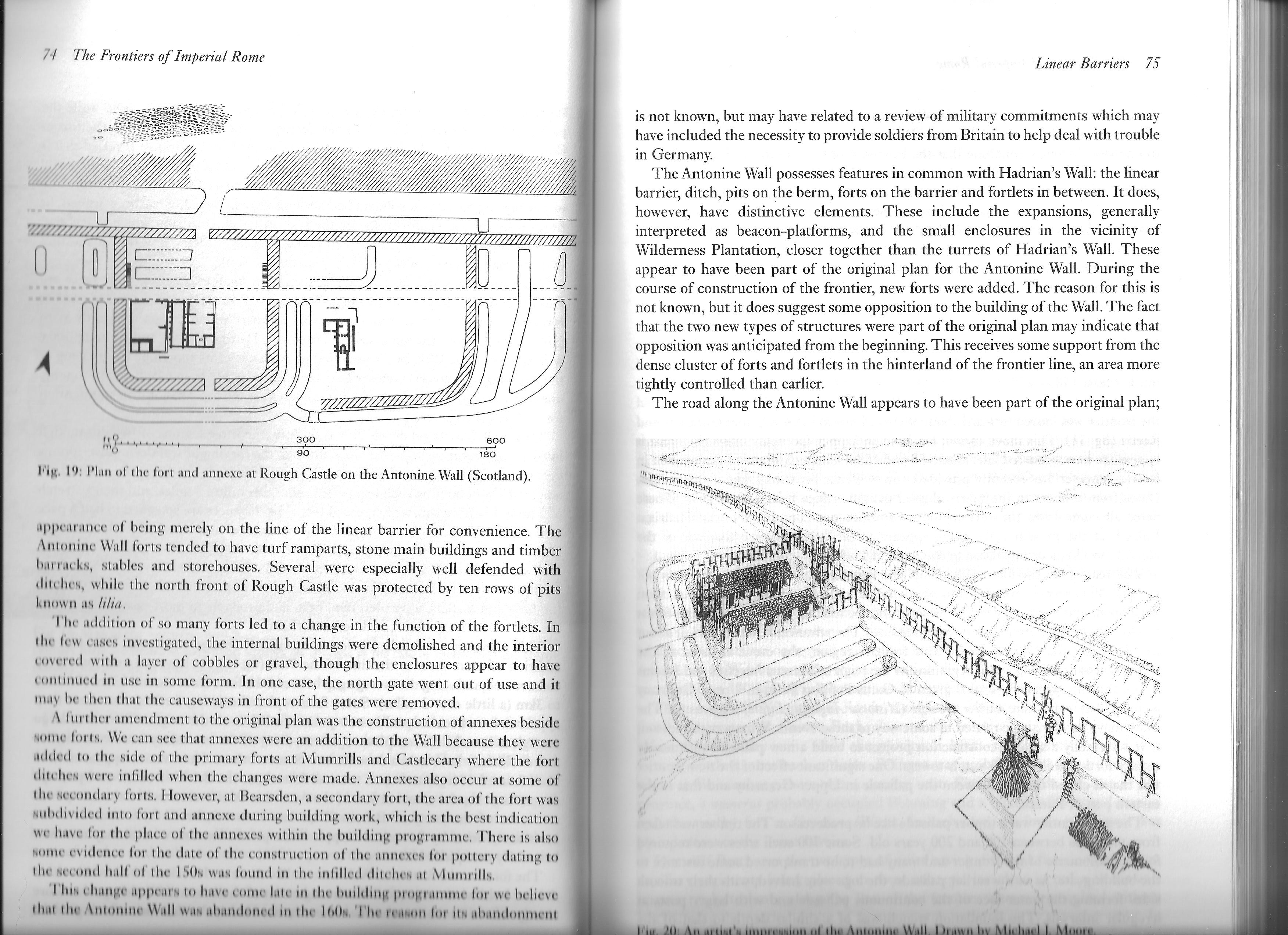

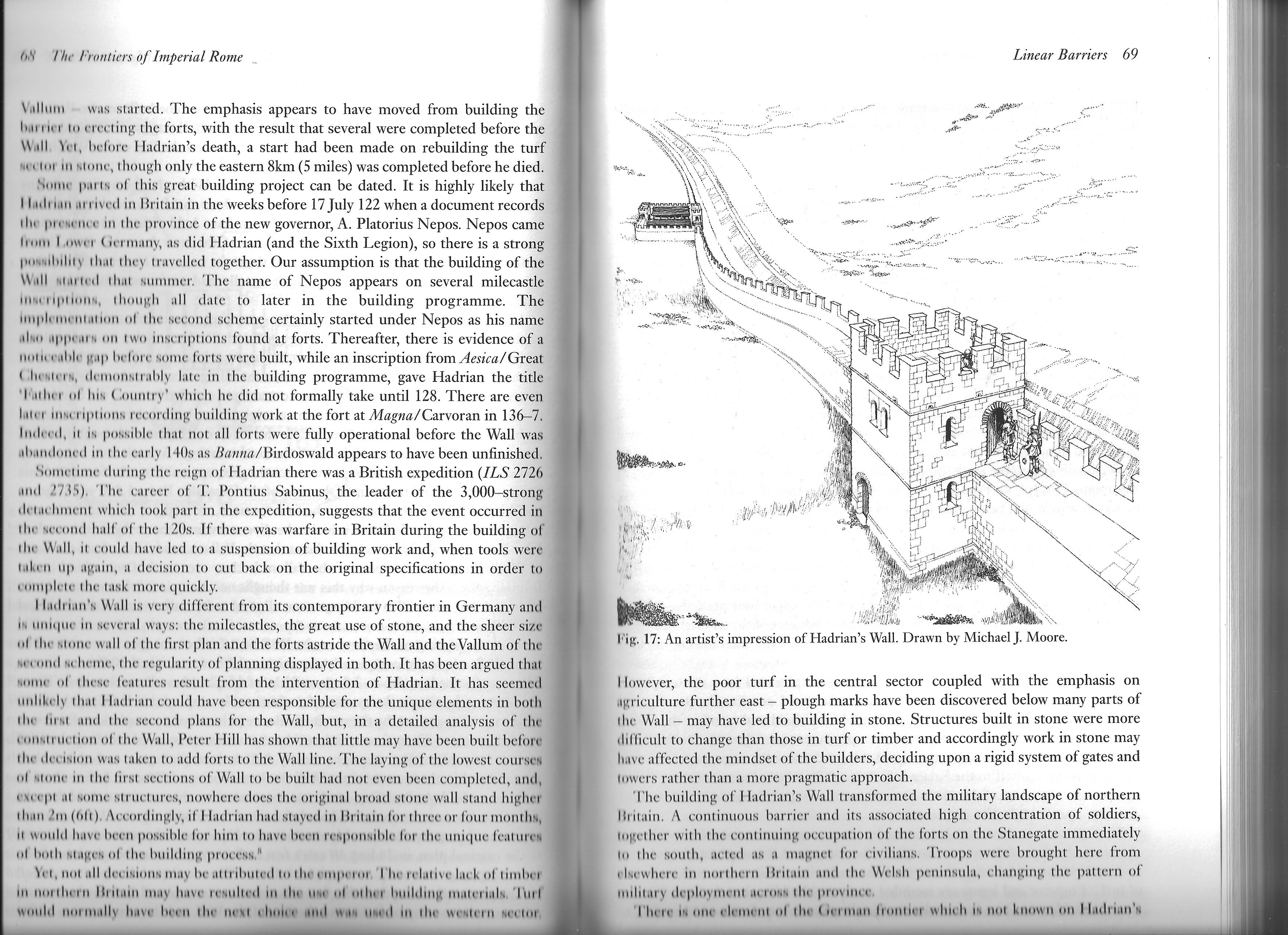

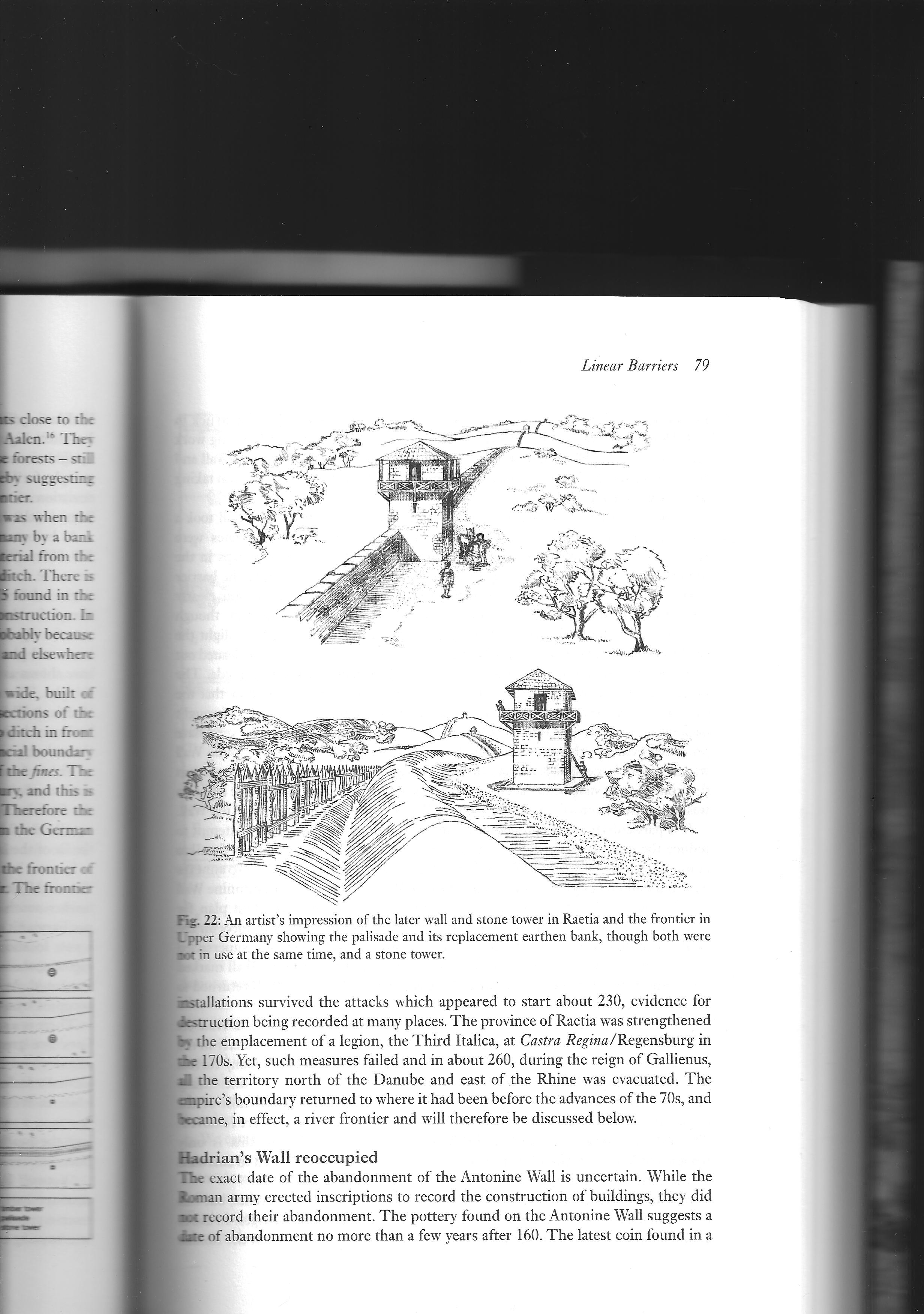

Well no other front did present a continuous stone wall with such an heavy military presence. Simply look at the forces deployed on the wall vs the lenght of the defended border, and add to that the three supporting legion further south, and then compare it with the density of troops on the German border (which used waterways and a berm + wooden wall with observation towers and camps as defense), the Danubian border (water + towers and camps), the desert border (fortlets and bases) or the Algerian side (unguarded low wall to direct traffic + fortresses) : you do indeed have the most heavily guarded border. You may want to check David J. Breeze's book "the frontiers of imperial Rome" (Pen & Swords 2011), for example figures 17, 20 and 22 :

-

1

1

-

-

Indeed, often such persons are only studied in passing or in limited articles, often old ones too. You may read a book I reviewed for this site a few years ago, that talks about second rank politicians of the 1st century BC (http://www.unrv.com/book-review/questioning-reputations.php) but they remain "famous" when compared to many.

The issue for many of the almost unknown characters of roman history you mention is the fact that so little survives about them so that we often have no more than one or two anecdotes, two or three lines or maybe a paragraph of Livius or another source. Then such characters become relagated to compendiums of curios, and lost to most peoples

-

Very good review, I'm myself about 3/4th in the book and I too have been quite surprised by the little room left to those who helped Octavian become Augustus. Agrippa in particular seems almost absent or at least made less important than he was, but also Maecenas. If you look at the index you see almost as many references to him as to Cicero. It is, I think, maybe due to the large introduction to the politics of Rome up to the death of Caesar, which might have been done in less depth without prejudice to the book.

Had I done the review I would also have mentioned the choice, argumented but not that common, of calling Octavian by the name of Julius Caesar through the book.

Still, good review and good book !

-

1

1

-

-

I've also signed up for this course, although it will compete for my time with a few other MOOC such as designing cities, making decisions in a complex world or introduction to submarine archeology... But I'll follow it

-

It's not as surprising as you might think : we have no ancient text about the ancient etruscan necropolis, nor about many large buildings or cities that awe us when we visit their remains. For example I don't think we have anything on the three republican temples of the Largo Argentina, in the middle of Rome. This tomb, here, was mostly a big mound of earth for the ancient and mostly a curiosity for the inhabitants of Amphipolis, with the lion at it's top, but many might not have known it was a tomb.

-

1

1

-

-

It's one of the outfit used by a German reconstitution group I think, or at least very similar to the one borne by those I saw in Belgium a few years ago.

The shield design is inspired by the Notitia Dignitarum if I remember well, while the helmet has a very ornate helmet from the hadrianic period if I'm not mistaken, the overal goal being to give an idea of the cavalry who demonstrated its talent in front of that emperor during his tour in the 120's -

As always

Right now I'm looking at Merida (Emerita Augusta), Grenada, Cordoba and Sevilla :

Right now I'm looking at Merida (Emerita Augusta), Grenada, Cordoba and Sevilla :

Seville archeological museum Seville Palace of the Countess of Lebrija Seville Metropol Parasol antiquarium Seville Italica Cordoue Archaeological site of Cercadilla Cordoue Great Mosque of Córdoba Cordoue Theatre Cordoue Roman Temple Cordoue Mausoleum Cordoue Roman Bridge Cordoue Colonial Forum Cordoue Forum Adiectum Cordoue amphitheater Cordoue Roman walls Cordoue Medina Azahara Grenade Alhambrahttp://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Emerita_Augusta

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/C%C3%B3rdoba,_Andalusia#Main_sights

-

1

1

-

-

Actually after posting it here I went back to writing the following parts : you can read the firsts results of this effort on http://www.alternatehistory.com/discussion/showthread.php?t=293937

Anyway I'm pleased you liked it

-

The inscription is in greek and says "Hermes" (ERMHS), the greek name of the god Mercury.

I don't think I ever saw the exact type which inspired this copy, but it seems a bit like the "Hermes and the Infant Dionysos" from Olympia (cf. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hermes_and_the_Infant_Dionysus )

-

1

1

-

-

You might like to read Christopher Matthew's "A storm of Spear" then, one of the very rare books that attempt to look at as many archeological remains and ancient representations of warfare as possible to reassess ancient greek warfare without the bias of previous authors and then to confront the "truth as it comes from the ground" with the various theories floating around on the topic.

"Men of bronze : hoplite warfare in ancient greece", edited by D. Kagan andG.F. Viggiano is also a nice read by the way, if only to see were the lines of scholarship were drawn in 2008 (a pity the book came out 5 years after the conference...)

-

thanks for the suggestion, I'd not thought about Italica (actually I misplaced it on the map, putting it rather in Murcia area) despite the fact it's Trajanus and Hadrianus' birth place !

-

Hi everyone !

As I'll be giving a talk at a Madrid conference next october I decided I'd be having some side vacation in southern Spain. I have 3 or 4 days that I can spend there, and I intend to make the most of it, helped by the fact my plane would leave Sevilla at around 8PM.

So, my call to you all : do you have any roman themed recommendations in that specific area ?

-

1

1

-

-

I always tell the people I walk through my city of Brussels that they are in for "the biggest surprise the city has to offer" when I get to the Manneken Pis, but people do actually ask to see it so I can't escape it. As for the rest of the list, I can understand why people would put Stonehenge in, as pictures make it more impressive than it is for those who do not think about what they are seeing, and the same might be true of the Pyramids. As for those, when seen from the right angle, in 2004, you could still believe they were alone in the middle of nothing...

-

Actually I do have some texts (including a short novel, published by a free magazine, and a full lenght novel looking for a publisher) but they are in French, although I did sometimes play with timelines on alternatehistory.com. One such game, never finished though, was about a different Hadrianic reaction to the death of Trajan. So please forgive me the broken langage (you may say I did massacre your langage and I would not take offence), and if possible enjoy this piece :

Syria, autumn 117 CE

As tired as Publius Aelius Hadrianus Buccellanus might be, he knows his day is far from over. He has just finished a tense meeting with his concilium, during which the fate of Lusius Quietus, the untrustworthy legate of Judea, has been sealed. With the orders sent earlier to Publius Aclius Attianus, the præfectus prætorio, Hadrianus is confident that his rule will not be challenged in the immediate future, which only leaves the question of what to do for the long term destiny of the imperium.

For now peace had been restored in the East. The Parthian had been severly beaten, their armies shattered, numerous cities taken and plundered. The Jewish revolts in Judea and in various other cities of the empire have been crushed, with many of those blasphemous deniers of the gods killed by the legions or the regional authorities.

But peace is always fragile. The conquest of Dacia is still fresh, and there are other areas at risk from a barbarian invasion. Britannia, of course, is still partly free. Germania, as always, is a threat. Plenty of parts of the Danubian border are wide open to raids and even outright invasion, as he well knows since he did survey them in the name of the late imperator Trajanus.

Augustus, be he blessed in his eternal glory, had said that the Empire’s borders where to be secured, conquest to be shunned. Well, that had not been the vision of Trajanus, conqueror of Dacia and of Parthia… But would it be his policy ? He had already ordered a withdrawal from many part of the newly conquered territories, to insecure with their rear in full revolt. But should he do more ? Fortify what he could, abandon what he could not hold ?

A cup of wine in his hand, the emperor lost himself in his thoughts before finally falling asleep from the wine and the exhaustion, but not without taking some decisions first…Oescus, Danubian border, autumn 117 CE

Publius Aelius Hadrianus seats enthroned in all the imperial glory, the commanders of the Danubian armies seated around him. The praetorium is a huge wooden building first constructed to hosts the headquarter of Hadrian’s predecessor, Trajanus, during his second dacian war.

Here Hadrianus has been a general amongst many, but he is now the absolute ruler of the Empire. Many roads lay in front of him, and only he will make the decision on which one to take.

In front of the assembled generals, a large map of the empire stood up, small flags and colours showing the extent of the empire and its various forces with an estimation of their respective strengths. A huge concentration of force was still present in the east, leaving the Rhine dangerously under guarded. In some places the borders where on riverlines, as on the Rhine, but much too often they were not. Dacia was exposed to the Roxolani and to the Iazyges, and there was a huge gap between the Rhine and Danube garrisons where barbarian pressure could splinter the roman defenses.

The emperor rose from his throne and felt all eyes looking at him. Walking slowly, he approached the huge map, his purple mantle falling on his shoulders the only noise to be heard. He showed them.

Two large scale offensives, both in the Danubian area, using forces freed by the end of the campaign in the east. Four enemies they knew well, two of them who had been diminished by the recent wars of Trajanus. The Roxolani and the Daci would be attacked from across the Danube , from the east, and pushed toward the north and the tribe of the Carpi, where they would be all pushed to the other side of the river Porata.

The Legio I Italica and XI Claudia would sparhead the attack with some detachments from the XV Apollinaris and the XII Fulminata brought from Cappadocia. The legio V Macedonica would serve as anchor for this movement while the XIII Gemina would protect the eastern side of the lands taken by Trajanus.

At the same time, on the other side of Dacia, XIV Gemina from Carnuntum, the II Adiutrix from Aquincum and the IV Flavia Felix would attack across the Danube from the west and the south, the VII Claudia protecting Dacia on the western side, the forces crushing the Iasyges to push them toward the mountains held by the Osi and the Cotini.

The Quadi and the Marcomani had been quite enough those last few years to so diminish the forces protecting Noricum and Pannonia. It was a gambit, but a reasonable enough one.

Hadrianus himself would lead the Iazyges offensive, knowing the land well from a previous mission in the area. Those two operations would significantly diminish the total length of the border, with mountains and rivers to shore up the future defenses.

Two or three years of campaigning would probably see the border put on the Porata of even the Tyras, giving numerous lines of defense against future raids from the steppe peoples.

His generals agreed. It was a sound plan, and would bring good agricultural land in the hands of the Empire, lands which would provide them with nice new estates.

And in three or four years they would be able to turn their sight back toward the east and Parthia with seasoned soldiers at their back. Yes, they liked the plan they were seeing.Apulum, Dacia, Spring 118 CE

Caius Cassius Voltinius looked at the agitation in front of the door of his praetorium tent. His legion, the XIII Gemina, had been cut in two units : one had been left in the base of Apulum, along with an unit of auxiliaries, while two third of his forces and two cohorts of auxiliaries had moved south toward Romula Malva where they had set a temporary camp. Their task was simple, as they were to guard a river against any barbarian that would be pushed in front of them by the men of the I Italica coming across the Danube at Novae.

They would then go north toward the mountains where they would prevent enemy incursions, pushing them toward the forces of the reinforced XI Claudia and of the V Macedonica which would try to trap them as the cork on an amphora or the anvil where the hammer would be the combined forces of the I Italica and the XI Claudia. Simple and efficient, if the Roxolani cavalry was prevented to unite and destroy a legion in the plains…

Yet Voltinius was confident. The memory of their crushing defeat at the hands of Trajanus left the barbarian fearful of the power of the legions, and many would flee rather than suffer the wrath of the legions. Grain had been brought from Egypt and Africa to granaries of the bases at Novae, Durostorum and Troesmis through the ports of Odessus, Tomis and Istrus, ensuring a good provisioning of the forces of the eastern offensive.

On the other hand the plan to simultaneously attack on the western side of the province to beat the Iazyges seemed a bit risky to the veteran legion commander. Of course large forces were brought to bear against the enemy, and the land was rather suitable for the kind of operations planned by the emperor, but was it not tempting the Gods than to ask for two victorious major campaigns at the same time in such a small area ?

He was sure that wheat and oat had been brought in large quantities to the fortress of Viminacium, Singidunum and Aquincum, and that logistics would not be an issue, but would the forces deployed to defend Sarmizegetusa, Napoca and Porolissum be enough to serve as anvil for the western hammer ? He hoped he would not have to turn his forces in a hurry toward this area…

As a soldier led his men toward the parade ground for some exercises, Voltinius shrugged and turned his attention to the state of his forces. This century was not full strength, he would have to check on the day’s sick list…Somewhere between Aquincum and Porolissum, near the Tisia river, late spring 118 CE

The campaign was going well and the emperor was pleased. Hadrianus was on his warhorse, relishing the good feeling that riding a powerful animal in company of a troop of mounted veterans always gave him.

The season had started in late march by the building of a large bridge across the Danuvius, actually two bridges to and from a small island in the middle of the river which allowed for much less efforts than initially planned for this step of the expedition.

He was followed by about twenty thousand men, mostly forces from legio XIV Gemina from Carnuntum and II Adiutrix from Aquincum itself and a large amount of auxiliaries coming from as far as Gaul and Britannia, recalled during the winter.

A force of about ten thousand more infantrymen was coming from the south, starting near the panonian capital of Sirmium and the bases at Singidunum in two collums ravaging the lands between the Danuvius and the Tisia, funneling the barbarians toward his force while being supported by the Danubian fleet.

Barbarian villages burned, women and children were killed or sold into slavery, and nowhere the men of fighting age were given the opportunity to regroup.

Still, the Iazyges made up a powerful tribe, and he must not underestimate them. He suspected that many of their warriors would be able to retreat behind the Tisia, on the Dacian side of the river, and might try to launch an attack against Porolissum or another of the recently founded cities of the province…

A dispatch bearer appeared and went for one of his aide. Probably something about a village destroyed, or a site found for the night’s camp… The area was far less densely wooded than the northern Germania, a good thing too if his plan was to succeed and if he were not to succumb to the kind of trap that had killed le legatus Varus in the time of the divine Augustus.

Hadrianus idly wondered for the umpteenth time whether he had made a good decision to attack across the Danuvius instead of launching his forces from Dacia toward the anvil that the river would have been. It had been a hotly debated question in the previous year, when the plans had been drawn, and he knew many officers were still uneasy about it.

Yet Hadrianus found it the best way to proceed, Dacia not being strong enough yet to support so many legions at once. Besides, the new province being ravaged would not really be a major loss, and the area, settled as it was with recently retired veterans and guarded by two legions and various auxiliaries, would prove to be a hard nut to crack for the Barbarians…On the bank of the Tisia, early spring 118 CE

The two forces were deployed face to face, between their two camps. On a rather narrow plain flanked by forests on one side and the river Tisia on the other, closed by the camps of the two armies, nearly eighty thousand armed men faced each other. On the roman side, three legions stood under their eagles, flanked by various auxiliary units.

In front, the Barbarian seemed to be three times as numerous as the Romans, at least forty thousand warriors, mostly warriors on foot armed with long spears, swords and shields or hunting bows. Behind them, on the walls of the makeshift camp made of chariots and barrels, many women and children looked at their menfolk. They knew it was all or nothing: the river was too wide to cross easily, and they were no boats available. Beside the Romans had put cavalry and a small infantry detachment on the other bank of the river, ready to kill anyone who’d try to escape.

It had taken some three months, but the legions had cornered a large party of Iazyges before they could escape to the northern mountains. Hadrian’s forces had closed the way and pushed people toward the south were two columns supported by part of the Danubian fleet were coming.

Finally the various forces had met. A night march had let the Romans regroup, the southern force coming to the Emperor’s camp. A complex, tricky manoeuver, but a successful one that could only succeed thanks to the complete dominance of the Tisia river by the fleet.

A tower had been built on the field of war, on which hung the imperial standard. Hadrianus wanted his men to see him, but he also wanted to keep some control on the battle. About two third of the Iazyges people was trapped and the day’s battle would decide their fate.

The Romans had arrived before the Iazyges, and the site was the one that best suited them in a four days of march radius. They had planted some traps on their flank to prevent an attack from outside the woods, and artillery had been carefully sited to help soften any barbarian charge in the front. The men were confident, after a rather easy walk into enemy territory.

The Iazyges had been completely surprised by the offensive, which had begun quite early in the year despite the rivers still being inflated by water from the melted snow. Boat bridges had been built in sections and quickly launched across the river, benefiting from experience on the rivers of Mesopotamia and Dacia in the previous years.

Loot had been plentiful, with many new slaves being captured and many golden ornaments found in the huts or on the bodies of fallen warriors. But now the time to pay for it all had come, and it would be settled in blood. Still, the favorable terrain and the roman discipline of the veteran forces would be more than able to cope with the undisciplined barbarian onslaught, or so hoped every roman soldier that day.

Silence reigned in the roman lines, except for the occasional bark of a centurion berating one of his men. The almost total lack of cavalry in this battle meant that no horses were neighing nervously, and most men simply waited for the battle to begin. The priests had made their sacrifices, auspices were deemed favorable. The Emperor himself was with them, which meant he might see and recompense brave deeds. His sight alone gave strength to his men.

On the other side of the field was a large body of men. Thousands upon thousands of warriors milled around, loosely grouped around their war leaders. Some men carried armor, brilliant chainmail and golden helmets decorated with strange devices in the shape of animals or with brilliant feathers, but most only wore a tunic and long pants.

The noblest warriors did also have golden armlets that would do fine as trophies for those who would slay them. Many carried a shield, either a small round piece of wood with a central metallic umbos or a larger whicker shield. Few carried shields made in the Gallic fashion. Tall spears and long swords where the weapons of choice of those men.

While the Romans were mostly silent, the Iazyges were rather noisy, loudly calling names at their enemies. Sometimes some men would go out of the crowd and call out for a duel, never answered by the legionaries. One man, braver or more insane than the other, approached the Romans before being speared by a ballista bolt than went through him and fell a few paces before the barbarian lines. First blood had been shed.

The barbarian answered by dressing their lines while beginning their war chant, hitting their shields with their blades. It was not the baryttus of the northern Germans, but it was similar. Behind them the women and the children took on the cry, adding their voice to the waves of sound that traveled the field toward the legions.

There it was met by the prayers of the soldiers, and then the hymn to Apollo was sung. The deep voices of the legionaries took the chant in Latin, each man with his own accent bearing witness to the size of the Empire. From Gaul as well as from Syria, from Mauretania as well as from Italy, from Achaia as well as from Egypt, they had come on this Danubian field of this day to fight for a city most had never seen, in the name of an Emperor which few had ever seen before this campaign.

The Barbarians began to advance toward the Romans, still chanting. Suddenly the noise of many cords suddenly released sounded in the back of the soldiers, followed by the sound of large projectiles rushing toward the enemy lines.

Ballistae shot their bolts which impaled many men at once, larger round shots falling from the sky and rolling on the ground, breaking bones and making men howl with pain. Still the great mass of the enemy kept coming, like a beast whose wounds would close as soon as they appeared.

Legionaries readied their heavy pilum, the throwing spear designed to break the shield formations of the enemies that was their trademark as much as their heavy lorica segmentata. Auxiliaries made sure their chainmail was falling correctly on their shoulders, checked their swords in their scabbard, prayed one last time to their native gods

Taking a few steps to get more throwing power, the legionaries hurled their spears toward the enemy, unsheathing their blades while the dark cloud of iron and wood fell on the Iazyges, sowing death deep in their formation. Still they came, pushed forward by mass as much as by will. The legionaries kept going, their line an impeccable front of heavy shields and metal helmets, the points of their gladius visible in the gaps between the scutum of the men.

A huge noise resonated in the field when the two armies connected. Arrows flew above the first lines of each side, falling down onto the soldiers waiting to get into the meat grinder that was called battle. Men fell to the ground, some slain outright, others still screaming while their comrade in arms walked upon them or their enemies stabbed them so that they may not do any harm any longer.

In the tower where Hadrianus watched the fight, the tension was palpable. The officers of the high command were happy to see that the roman line had held to the shock. Not it was to be seen if they might last long enough to put the enemy in flight. Still, orders had to be sent. Flags from the top of the tower communicated them to the other side of the river, where a horseman saw them and began to run his horse toward the south. The trap was now sprung…

For Hadrianus had planned well and chosen his terrain while knowing that he had no room to deploy his cavalry in the normal way. For this reason he’d used his fleet to carry a part of it on a small island in the middle of the river, and he had now given the order that they cross again and fall on the back of the Barbarians, a party of auxiliaries following to secure the enemy camp while everyone was watching for the main action. Grinning somberly, the emperor kept watching the action in front of him. His infantrymen only had to hold for three hours…On the bank of the Tisia, early spring 118 CE

Seven days had passed since the large battle that had seen the destruction of any coherent Iazyge defense had been won. All around the imperial tent wounded soldiers walked in order to carry some duty or just for the pleasure of walking and being alive.

While not so many Romans had been killed, only some four hundred men, the wounded were numerous, hundreds of men having lost limbs or been severely hurt in another way : eyes gouged by the iron of a spear, face cut by swords’ points, bones broken by the pressure of the bodies of the warriors behind and in front of them…

Still, they were much better off than their enemies. Thousands of their best warriors had died in the front line, unable to pierce the wall of wood and steel and flesh of the legions, unable to overwhelm the Romans despite the large numerical advantage they held.

The narrowness of the plain had constricted them, hampering their moves and limiting the number of arms they could bear against the legionaries and their auxiliaries, and the Romans’ discipline and almost mechanical way of killing had meant they could keep fighting much longer than the Barbarian. At one point they had even made a retreat of half a hundred paces in order for fresher men to take place on the front line, breaking contact for a few seconds before the stunned barbarians could react.

And then the cavalry had come. Not many men attacked the barbarians from their back, only about a thousand horsemen, but they were enough. They had spread enormous fear in the heart of their enemies who began to flee under the despairing calls of their women and children already being taken captive by a force of auxiliaries that had crossed the river with the horsemen.

Hadrianus had been remembered of the divine Caesar’s description of the final defeat of the Helvetii. Here too he’d captured a very large crowd making a full people, with many of their warriors killed or taken captive. But, unlike his predecessor, he did not intend to set them free and to give them a new land. The proceedings of the sale of the whole lot as slaves would greatly improve the Empire’s finances as well as his own. Or at least such had been his initial thinking…

It had been one of his subordinate who had come with the innovative idea: why sell them all to others who would get rich from their labor when he could as well settle them on imperial lands currently unoccupied where they would be able to build cities and pay taxes forever, taxes that would go to the treasure instead of into the fortunes of the senators.

Also they could be settled in distant places where they would cause no troubles and serve the empire, especially if they were to be isolated from their free brethren. Had not the divine Caesar done something somewhat similar when he had ordered the Helvetii back to their abandoned lands where they had served as deterrent to Germanic raids on northern Italia ?

The debate following this novel idea had been fierce, to say the least. Yet a solution had finally been found, with all the captive without consort and all the couples without children being sold into slavery, the rest, being mostly the younger couples, to be split into about a hundred groups of some twenty families that would be sent to Syria, Mauretania and Britannia where each group would found a village to work the land and later to provide recruits for the local auxiliary forces.

Those lands had all known recent unrest and could benefit from peoples that would be grateful for the opportunity not to end up in slavery… while also being loyal out of fear of being killed because they’d be the stranger taking good lands from the locals.

Now that this issue had been resolved the emperor had also to plan his next move. He had not expected such a swift and crushing victory on his enemies in the west. He could probably begin the real work of settling the area with roads and fortresses as well as plan for more civilian settlements. But should he set the territories into a new province or simply add it to either Moesia or Dacia ?Near Piscul, Dacia Inferior, late spring 118 CE

Caius Cassius Voltinius was furious. That stupid commander would see them all killed before this war would end, and it would not be Rome that would be the victorious party. First he’d wanted to wait for news of the imperial campaign to the west before beginning to move his forces. Then he’d gone with a slow, meticulous, cleaning of the area, instead of following the initial imperial plans.

Instead of coming vigorously from the south with two legions and supports and push the enemy toward the forces launched from Troesmis, he’d decided to use the numerous rivers of the area as limits to sectors he wanted pacified before moving on to the next one. Thus had first the I Italica moved across the Danuvius, going toward the north east, alone in enemy territory, while the forces under Voltinius command had also gone toward the north.

The I Italica had suffered casualties in many skirmishes, it’s progress hampered by cavalry raids by the Roxolani, mainly horse archers darting in and out before anyone could react. The legion had not even received all the cavalry support it could have, so they were unable to retaliate. Then the XI Claudia had also launched its attack, about one month and a half after the garrison of Novae had left. From Durostorum they had gone north, meeting up with the I Italica neat the Dacian citadel of Piscul, well to the west of their intended march plans.

Voltinius himself had received orders to reinforce them there, traveling with his half legion and most of his auxiliaries. They were now some twenty thousand men, about a fifth of them cavalry, about to fight against a massive Roxolani army of some thirty thousand men, at least two third of them being cavalrymen.

Voltunius still remembered his shock when he’d learned, more than twenty five years earlier, how the legio XXI Rapax had been destroyed by the Roxolani. Possibly some of the men he was now going to fight had been present that day, sinking their iron into Roman blood.

The Romans were thus had about half the strength they should have been, and had been cornered in a place where they would have to give battle, unable to wait for the forces from Troesmis which had finally left their camp and were coming from the north-east toward their position, meaning that while they would probably not be able to help in the coming battle, they would probably be able to crush those victorious Roxolani left alive after Voltinius’ men death. And thus providing their commander with all the glory... and the loot !

Voltunius chastised himself. Such way of thinking could only lead to defeat. It was not the Roman way. After all did not the legio III Gallica succeed in destroying a force of 9000 Roxolanian cavalry in the time of the cursed emperor Nero ?

With those thoughts in mind, he went to the meeting organized by his fellow legati to plan for the next day.-

1

1

-

-

That point about Paris is good. You might say the same about Odysseus. But what about Philoctetes and Hercules who's bow Philoctetes inherited? Then there is also Teucer who is nothing but admired in the Iliad, and although archery comes almost last in Book XXIII, the funeral games, the javelin throw is the next and final competition and I wouldn't say that it is despised.

You are right of course, I only gave Paris as one example, but if you look closely at the Illiad you have the same kind of ambivalence surrounding all those archers characters : Odysseus is dodgy, although he can hold his place on the battlefield. Philoctetes is diseased, left alone on his island until it's no longer possible to leave him there, the will of the gods being too strong. Teucer is indeed admired, but he fights from behind the shield of Ajax : in all cases the archers are not "straight arrows" if you'll pardon me the pun.

-

On the other hand a thread I follow on the Skyscrapercity.com message board is about archeology of Sicily and they often post scans of newspaper articles talking about new discoveries or sites newly opened to the visitors or exhibits in museums or some sites' shameful condition. So I think it might also be a question of which sources you follow : big media might not talk a lot about it but the more local newsproviders might well. The only thing that will come to the forefront is the occasional world class discovery like the cup of Pericles that's just been announced today (for those not aware : a 5th century BCE ceramic cup that bears inscriptions that strongly suggest it was used at least once at a drinking party by Pericles when in his 20's had been found, ironicaly enough, in Sparta Street, northern Athens, during works for a new parking).

-

1

1

-

-

Bassae and Cyrene apart, I've had the opportunity to visit them all. Each is different, each has it's plus points, and indeed there are not many out there that could be added to the list with visible remains, although I would add Aegina and possibly one or two of the Turkish one.

-

you can still see the ditches surrounding Stonehenge when you visit the place and look around you while going to the monument, instead of only starring at it. As for WW1 trenches, you can of course still see them even at ground level, although a lot was backfiled and is thus only visible from the sky. You can actually see individual artillery shell holes from the sky all along the fronts of WW1. You also have various other ditches that can be seen in many other places, including some from the roman time : think of the Antonine wall for exemple.

Another typical kind of ditch is the surface iron mining ditches from the iron age you can often find in the forests of France or central Europe.

-

Yes I do. But also because my mother loves cat's and asked me, years ago, to take pictures of cats on all my journeys, so I do.

-

Thanks

I do love Art Nouveau, it's my favourite "modern" art form, at least for the art that finds it's way to museum, in part because it was the last massively artisanal form of art, and one of the few total forms of arts (architecture, painting, sculpture, ...)

I do love Art Nouveau, it's my favourite "modern" art form, at least for the art that finds it's way to museum, in part because it was the last massively artisanal form of art, and one of the few total forms of arts (architecture, painting, sculpture, ...)

Question about Latin and Trade

in Lingua Latina

Posted

well first you have to define the period at which you're looking, and then the region as the trade dynamics were not the same everywhere.

For instance in the Republican period we have roman traders going all around Gaul, They would teach some latin, or use translators that might teach their skill to others. But we know from Caesar that there were more chances that the Gauls might now the greek alphabet (see the Helvetii's tablets after their defeat).

In the imperial period you had both traders going out of the empire into the wilderness, and traders from barbarian lands comming to outposts to sell their wares. The roman traders would go to villages/town and then bargain, either with the help of a translator or with people who, by their elite statute might already know latin thanks to previous association with the empire (Arminius had been in the Roman army for instance, so he spoke latin). Others might then want to learn the langage to be able to show they too can be part of this elite. Soldiers might also become traders themselve after their time serving the army, their "pension bonus" providing them the cash to establish their business and their former comrades becoming their new clients.

Finally the foreign traders might also learn latin in inns and taverns inside roman territory...

Also remember that the langage situation could be hyper-local : I remember visiting two cities on the Danube, some 50km from each other, one with all its epigraphy in latin and the other in greek...